Understanding physiology in yoga is crucial for a meaningful practice. It unlocks the deep connection between the physical body, breath, and the underlying energy systems. By exploring yoga's physiology, we not only learn how to avoid injury but also how asanas (postures) and pranayama (breathing techniques) improve our overall health and well-being.

If you’re looking for a solid foundation in physiology, this guide will bridge the gap between ancient traditions and the modern science of yoga, equipping you with the tools to enhance your personal practice as student or teacher and reap the many benefits of yoga.

What Is Yoga Physiology?

Physiology is the area of biology that deals with the normal functions of living things, and the functions of their organs or systems. When we refer to the physiology of yoga, we are talking about how yoga affects the functioning of the human body.

Understanding the anatomy and physiology behind your favorite yoga poses and pranayama techniques is the first step to a safe and balanced practice. But this knowledge also allows us to experience a deeper mind-body connection that goes beyond the mere physical practice of yoga.

How Does Yoga Affect Your Physiology?

Yoga Philosophy

Yoga philosophy offers guidance in various aspects of our life, whether it be relationships, spirituality, or health. These insights naturally influence physical health and wellbeing. For instance, practicing the Niyamas (habits) leads to positive changes in our diet and exercise, and even our hygiene and sleep habits.

The connection here is that our health and well-being depend on our physiology. They are, in essence, the same thing. Improved diet, exercise, and sleep will improve the function of our nervous system, digestive system, hormonal system, brain, muscular system, and more.

Yoga philosophy also encourages mental health strategies, such as gratitude, kindness, and generosity. Modern research has confirmed that these practices improve brain health, and are associated with lower rates of brain dysfunctions like dementia. The exact physiological pathway for these effects is still being researched, but it is known that positive mental health strategies can have a physical effect on the structure and function of the brain.

Therefore, it can be argued that both the physical practices and the philosophy of yoga contribute to its proven ability to interrupt the negative cycle of chronic stress and promote holistic pathways toward health and true happiness.

Yoga Practices

The physical practice of yoga asana was invented by monks as a way to improve the function of their organs and glands. This means that the yoga's original purpose wasn’t to achieve inner peace, but to influence the physiology of those who practiced it. These ancient practitioners believed that yoga poses improved the function of organs and glands by various means, such as the squeeze-and-release effect as well as by altering blood flow.

Modern scientific testing is slowly uncovering the physiological pathways that produce the long-recognized benefits of yoga. While small, these studies focus on the physiological effects of asana, pranayama breathing exercises, and meditation, producing stronger evidence of yoga’s profound power.

It’s important to understand that when scientific research investigates whether yoga has a certain physiological effect, it doesn’t simply ask people whether they feel better, although it may do that as well. Common scientific measurements include familiar tests like heart rate and blood pressure measurements, however researchers often collect meaningful details from a variety of scans and tests. For example, blood tests for studies into stress might assess the levels of numerous hormones and chemical markers like cortisol, catecholamines, glucose, hbA1c, triglycerides, and cholesterol, to name a few.

Such scientific details of physiology are too vast and complex to cover fully in an article (or even in an entire master's degree). So, to provide a comprehensive and clear overview of yoga physiology, this guide will address the practical and functional effects of yoga and outline the pathways leading to these effects.

Yoga & the Nervous System

Many of yoga’s benefits arise from the regulation of the nervous system. The nervous system is the body’s communication hub, carrying messages that control all the processes inside our body, as well as the movements we consciously choose to make.

The part of the nervous system that manages our internal organs and involuntary functions is the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS is regulated by a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. It controls cardiac function, respiration, digestion, hormonal balance and other reflexes like sneezing. The autonomic nervous system can be further divided into two main branches:

1. Sympathetic Nervous System:

Sympathetic nerve fibers use the neurotransmitter noradrenaline to increase blood flow in skeletal muscles and lungs, dilate lungs and blood vessels, and raise the heart rate. This is known as the "fight or flight" response. It is a natural function which prepares us to respond to or escape a threat, whether that threat is a lion or a pressing deadline at work.

2. Parasympathetic Nervous System:

The parasympathetic system regulates “rest and digest” responses, such as reducing heart rate and increasing salivation, lacrimation (tear production to hydrate the eyes), and digestion. When a perceived threat has passed, this system activates, bringing our body back to a state of calm.

In a balanced life, the sympathetic nervous system responds to stressors in a healthy and productive way and is balanced by the parasympathetic nervous system responding to opportunities for calm. However, many people are chronically stressed and find it difficult to shift out of the “fight or flight” mode even when a stressful event is over. Fortunately, yoga can help.

The Vagus Nerve

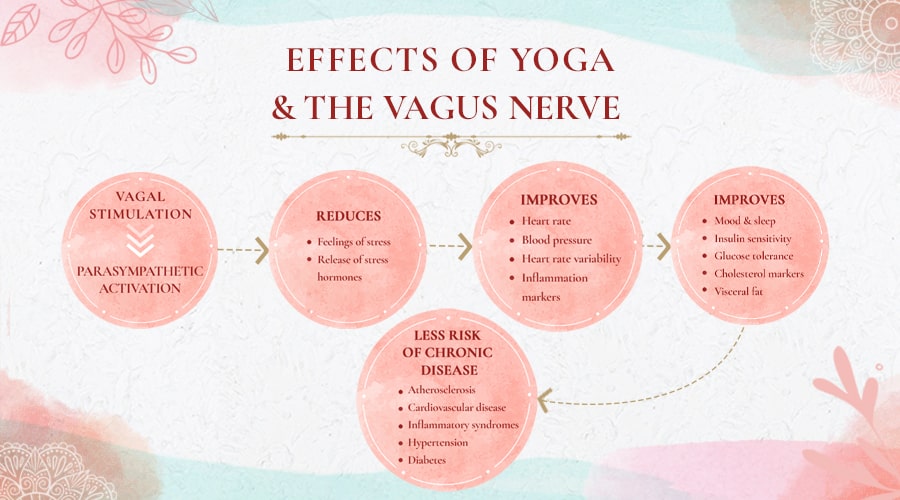

Studies suggest that yoga’s influence on the nervous system is largely due to stimulation of the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve acts like an information web between the brain and the bodily systems. It’s a major component of the parasympathetic nervous system, and stimulation of the vagus nerve promotes the parasympathetic “rest and digest” functions.

The vagus nerve collects information from across its large network of receptors in the airways, gut, heart, and blood vessels, to name a few. Either the brain or the vagal network itself then responds to the collected information by creating responses intended to keep our systems functioning in a healthy, balanced way.

We can influence the activity of the vagus nerve by altering the information those receptors collect. This is called vagus nerve stimulation.

Vagus nerve stimulation is a recognized health intervention in western medicine. Artificial stimulation of the nerve using electrodes has been approved as a medical therapy for refractory epilepsy, as well as for treatment resistant depression. Medical trials are ongoing for treatment of other conditions including heart failure, anxiety, chronic headaches, and more.

Without resorting to using electrodes, we can also use activities and practices like yoga to alter the information received by the vagus nerve.

How Does Vagal Nerve Stimulation Affect the Body & Mind?

Mechanoreceptors in the airways are among the most studied triggers of bodily change. These receptors signal airway expansion to the vagus nerve, which then adjusts its activity. So, when we breathe quickly or shallowly, our body gears up as if sensing danger. On the other hand, slow, deep breaths during yoga or pranayama practice tell our body that everything is fine, promoting calm and relaxation.

A second important pathway in vagal nerve activity involves mechanoreceptors in the heart and blood vessels. These baroreceptors are small sensors that monitor blood volume and pressure. If blood pressure drops too low, our body's 'fight or flight' system steps in to raise it. On the other hand, if it's too high, our 'rest and digest' system will trigger responses to lower it.

Poses like yoga inversions, including the Standing Forward Bend, are known to stimulate the vagus nerve and trigger parasympathetic activity. When the body tips upside-down, it puts pressure on these receptors, prompting the vagus nerve to slow down the heart rate and widen blood vessels, leading to relaxation.

Another crucial aspect of the vagus nerve is its position. With branches running down both sides of the neck, it connects our brain to our organs. It's uniquely situated outside the protective spinal column, making it vulnerable to stimulation from postures that compress the neck or throat tissues. Some believe that poses like the Sarvangasana (Shoulderstand) can compress the vagus nerve which leads to stimulations, inducing a calming effect.

Do All Yoga Practices Activate the “Rest and Digest” Response?

No, not all yoga practices include relaxing, calming elements. Some practices, like certain advanced pranayama exercises and Vinyasa Yoga, are meant to boost energy and heat, tapping into our 'fight or flight' system. But that's okay when done intentionally. Hatha Yoga, for instance, alternates between energizing and calming elements, training the body to transition between these states seamlessly.

Challenging and active yoga styles can also elevate heart rate and feel stressful, especially when learning a new pose. Initially, our muscles tense up, activating stress responses. But with practice, it can turn from a source of stress to a calming, restorative exercise. It's all about balance and progression in your yoga journey.

Get a free copy of our Amazon bestselling book directly into your inbox!

Learn how to practice, modify and sequence 250+ yoga postures according to ancient Hatha Yoga principles.

Movement & Compression in Yoga

The affects of yoga go beyond just the nervous system. Some benefits come directly from the physical movements involved, such as:

- moving different parts of the body

- applying pressure through specific poses

Think of when you press on a blood vessel during a pose; you're temporarily slowing down the blood flow. When you release that pressure, blood rushes back in, bringing a fresh supply of oxygen and nutrients. Ancient monks crafted yoga poses with this rejuvenating effect in mind, aiming to boost their health and well-being. Let’s explore how movement and compression in yoga can positively impact physiology.

Diaphragm & Lungs

Breathing exercises in yoga, like pranayama, are more than just inhales and exhales. They deeply engage our lungs and diaphragm. Since the diaphragm is closely connected to the heart and major blood vessels, deep diaphragmatic breathing can boost the flow of blood back to the heart. This movement also activates the parasympathetic nervous system, promoting a peaceful 'rest and digest' state.

Today, there's a wealth of evidence pointing to the benefits of yogic breathing, especially when it's deep and slow. Techniques like Ujjayi pranayama not only dial down the 'fight or flight' response to promote calmness but also improve oxygen uptake filling every part of the lungs. Meanwhile, these exercises fine-tune baroreceptors (small sensors that regulate blood pressure) making them more responsive. The heart also gets a boost from more oxygenated blood and a steady rhythm, eventually promoting synchronized, efficient heart functions.

Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is a network of tiny vessels scattered throughout the body, along with a system of lymph nodes and lymphoid tissue. Unlike the circulatory system, which has the heart to pump fluid, the lymphatic system depends on movement, gravity, and one-way valves to transport fluid towards the lymph nodes.

The lymph system collects excess fluid, cellular waste products, and bacteria that enter through our skin. This means that when the lymphatic system doesn’t drain fluids properly, the tissues swell and become uncomfortable. The lymph nodes and other lymphoid tissues monitor this flow and produce cells and antibodies that protect us from infections and disease.

The main responsibilities of the lymphatic system include:

- managing the fluid levels in the body

- reacting to bacteria and cancer cells

- dealing with cell products that otherwise would result in disease or disorders

- absorbing some of the fats in our diet from the intestine

Physical activity and muscle contractions drive the flow of lymph fluid through its pathways. Yoga asanas, with their diverse muscle engagements, enhance this lymph movement. Breathing exercises in yoga are especially beneficial for the extensive lymph system around the lungs. Additionally, yoga positions that invert parts of the body, like Legs Up the Wall or Headstand, help lymph fluid navigate areas that usually fight against gravity, making drainage more efficient.

Fascia

Fascia is a connective tissue that forms a web throughout the body. It forms sheaths around muscles and organs and connects them to each other. Within muscles, each bundle of muscle fibers is surrounded by fascia; within each bundle, individual muscle fibers are also surrounded by fascia.

When your body moves, tissues and organs move and slide against one another. There is increasing evidence that this movement increases the health and hydration of the fascia. Fascia doesn’t have a blood supply; it relies on movement to deliver fluids. Lack of movement then becomes a debilitating cycle, as dehydrated and stiffened fascia prevents easy movement of the body.

It’s believed that poor fascial health, and particularly fascial dehydration, may be responsible for much of the creakiness and stiffness we attribute to old age.

Plentiful and varied movement is good for fascial health and hydration. Yoga asanas offer a tremendous variety of movement patterns and positions. This variety of movement prevents the cycle of poor movement, ultimately boosting fascial health.

Joints

Our body's major joints are surrounded by a membrane that produces synovial fluid, ensuring smooth movement between bones and cartilage. This fluid not only aids in motion but also nourishes the cartilage, which lacks its own blood supply. Yoga asanas help preserve the flexibility and health of these joints. The Arthritis Foundation points out that exercises involving joint movement offer various benefits:

- Refreshes cartilage with oxygen and nutrients by pushing out and then drawing in water molecules

- Stimulates genes linked to cartilage repair

- Initiates autophagy, a process that breaks down and removes damaged joint cells

Moreover, the right exercises bolster the muscles, ligaments, and tendons supporting our joints, ensuring joint protection, longevity, and relief from arthritis symptoms.

6 Science-Backed Benefits of Yoga

It's clear then that yoga significantly impacts our bodily systems and functions. But, what benefits do they actually bring? Scientists have delved into the research and uncovered the following benefits of a regular, balanced yoga practice.

1. Balanced Mental Well-being & Stress Reduction

Yoga offers a holistic approach to achieving mental well-being. Research published in Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine (a peer-reviewed medical journal) reports that yoga can break the destructive cycle of chronic stress by relieving stress, improving mood, and promoting positive change in function and physiology.

By promoting relaxation, slowing breath, and centering attention to the present, yoga shifts from the sympathetic, "fight-or-flight" response, to the parasympathetic, relaxation response. Damping down the “flight or fight” response and balancing it with an enhanced “rest and digest” parasympathetic response positively affects neuroendocrine status, metabolic function, and related inflammatory responses, as well as our mood and energy state.

This is especially true for people who suffer from depression and anxiety. A study conducted in 2007, showed that yoga practitioners experienced an average raise of 27% in levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an important neurotransmitter linked to behavior and mood swings, during 55 minutes of asana practice. As a result, yoga for depression, combined with other medical treatments, is becoming a more popular and effective path to mood stabilization and stress reduction.

2. Cardiovascular Health

Yoga offers multiple heart-health benefits. One key advantage is stress reduction through parasympathetic activation. Engaging in gentle yoga and calming breathing exercises guides us into a relaxed state, releasing acetylcholine, a hormone that slows the heart rate. Regular yoga can therefore help stabilize the resting heart rate. Research also indicates that stimulating the vagus nerve can boost insulin sensitivity, decrease 'bad' cholesterol, and cut down harmful visceral fat stored deep within our bodies.

Moreover, a 2021 study revealed that a consistent yoga practice, combined with deep breathing, can lower both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in those with prehypertension, reducing the risk of hypertension and other heart-related diseases.

3. Insomnia and Sleep Quality

Gentle bedtime yoga and meditation is a useful method for improving sleep and reducing insomnia. By activating the parasympathetic nervous system, yoga practices calm the mind and body, reducing over stimulation and arousal before bed.

One study analyzed the effects of yoga on 21 patients with chronic insomnia disorder. The findings concluded that a tailored practice could be used as an alternative form of therapy to reduce symptoms and regulate sleep patterns.

4. Reduces Inflammation

Chronic inflammation is another health concern many of us suffer with. While short-term inflammation aids healing, long-term inflammation damages our organs and is linked to numerous diseases, from diabetes to auto-immune disorders. This persistent inflammation can lead to symptoms that resemble chronic stress, like body pain, sleep disturbances, mood swings, digestive issues, and even frequent infections.

Thankfully, practices like yoga, meditation, and breathing exercises can combat stress-induced inflammation. By stimulating the vagus nerve, these practices help reduce our risk of chronic ailments including heart disease and diabetes. Therefore, yoga's positive influence on the vagus nerve is a gateway to overall better health.

5. Improves Digestion

Practicing yoga for digestion can be an effective treatment for many. Some yoga poses put pressure on or squeeze the digestive organs, while others give them a good stretch. This improves circulation, allowing more fresh blood to get to the organs and improve how they work.

These movements help food move efficiently through our digestive system. Twisting poses, for example, are great for helping move food along and can relieve constipation. The way the diaphragm moves during breathing exercises can also give our digestive organs a gentle massage.

Additionally, the calming effect yoga has on the nervous system, along with its ability to promote overall well-being and alleviate digestive distress, makes it a highly beneficial practice for those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). A randomized trial exploring the impact of seated yoga poses on young patients with IBS found that individuals experienced significantly lower gastrointestinal symptoms and emotion-focused avoidance after the yoga intervention.

6. Enhanced Physical Health & Strength

Among the evident benefits of yoga is improved flexibility and strength. In Hatha Yoga, our body moves through various warming-up exercises and challenging asanas. These movements lengthen and develop our muscles through eccentric contractions, such as the hamstrings in Standing Forward Bend. The isometric contractions of the muscles in stable poses like the Shoulderstand or Plough Pose encourage strength while stretching the fascia. Additionally, in maintaining a position for a period of time, we condition our muscle spindles (stretch receptors that measure the length of resting muscles), training them to withstand greater strain both before and after the stretch-reflex.

Therefore, continuous practice of yoga gradually loosens muscles and connective tissues around bones and joints. This can result in fewer aches and reduced pains. Furthermore, gentle yoga poses bring more fluidity and flexibility into the joints, strengthening the muscles around the joints and providing more stability. This reduces stiffness and inflammation, protecting the joints against conditions like arthritis, osteoporosis, and chronic back pain.Final Thought

If the practice of yoga is to move you towards a state of contentment and eventual enlightenment, it must also move you towards good health. Since ancient times, yoga has included philosophy and physical practices intended to improve the function of the body and its systems, organs, and glands. Modern research is slowly catching up with ancient knowledge, providing scientific explanations to the effects monks discovered centuries ago. Ultimately, the physiology of yoga is simple: yoga can transform your body and your mind.

Sources - books

Hatha Yoga for Teachers & Practitioners - https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/9082705613

Sources - research reports

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6137615 - How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5709795 - The physiological effects of slow breathing in the healthy human

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009506.pub4/full?highlightAbstract=yoga%7Ceffects%7Cof%7Ceffect - Yoga for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3482773 - Physiological Effects of Yogic Practices and Transcendental Meditation in Health and Disease

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17658122 - Chronic stress and insulin resistance-related indices of cardiovascular disease risk

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6189422 - Breath of Life: The Respiratory Vagal Stimulation Model of Contemplative Activity

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4017164 - Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Get a free copy of our Amazon bestselling book directly into your inbox!

Learn how to practice, modify and sequence 250+ yoga postures according to ancient Hatha Yoga principles.